How many founders quietly achieve meaningful exits without venture capital

Most founders in tech believe that venture capital is the only realistic path to an outstanding outcome.

Not because they’ve evaluated all the alternatives and chosen it deliberately – but because it’s often the only path they’ve ever seen modeled. Funding announcements are public. Unicorns make headlines. Venture-backed success stories dominate the narrative.

Bootstrapping, by contrast, is quiet. Profitable companies don’t issue press releases. Acquisitions of capital-efficient businesses rarely make the news. And so many founders internalize a subtle but powerful assumption early on: that without venture capital, the upside is capped.

That assumption is wrong.

There is a large, active, and mostly invisible market for bootstrapped and lightly funded companies – one that produces outcomes that are meaningful, founder-friendly, and in many cases life-changing. The difference isn’t that these outcomes are smaller. It’s that they don’t fit the venture narrative.

The Mental Model Gap

Most tech founders operate with a very narrow map of how success is supposed to unfold:

- Raise a seed round.

- Raise a Series A.

- Continue growing fast enough to justify the next round(s).

- Eventually exit at a scale that makes the whole journey “worth it.”

There’s a time and a place for this approach, but for most businesses (and therefor founders), this does not end with a happy ending.

Venture capital is a specialized tool designed for a specific outcome profile: a small number of extreme winners that return an entire fund. That constraint shapes everything downstream: growth expectations, risk tolerance, dilution, exit size, and timing.

Outside the venture ecosystem, companies are judged very differently – on cash flow, durability, and how well they work as businesses rather than their potential to become a multi billion dollar company.

The problem isn’t that founders choose VC.

It’s that many don’t realize they’re choosing a very specific future when they do.

The Ownership Math Most Founders Never Do

When founders think about exits, they usually think in company-level terms: What could this business be worth?

What should also be considered are founder-level outcomes.

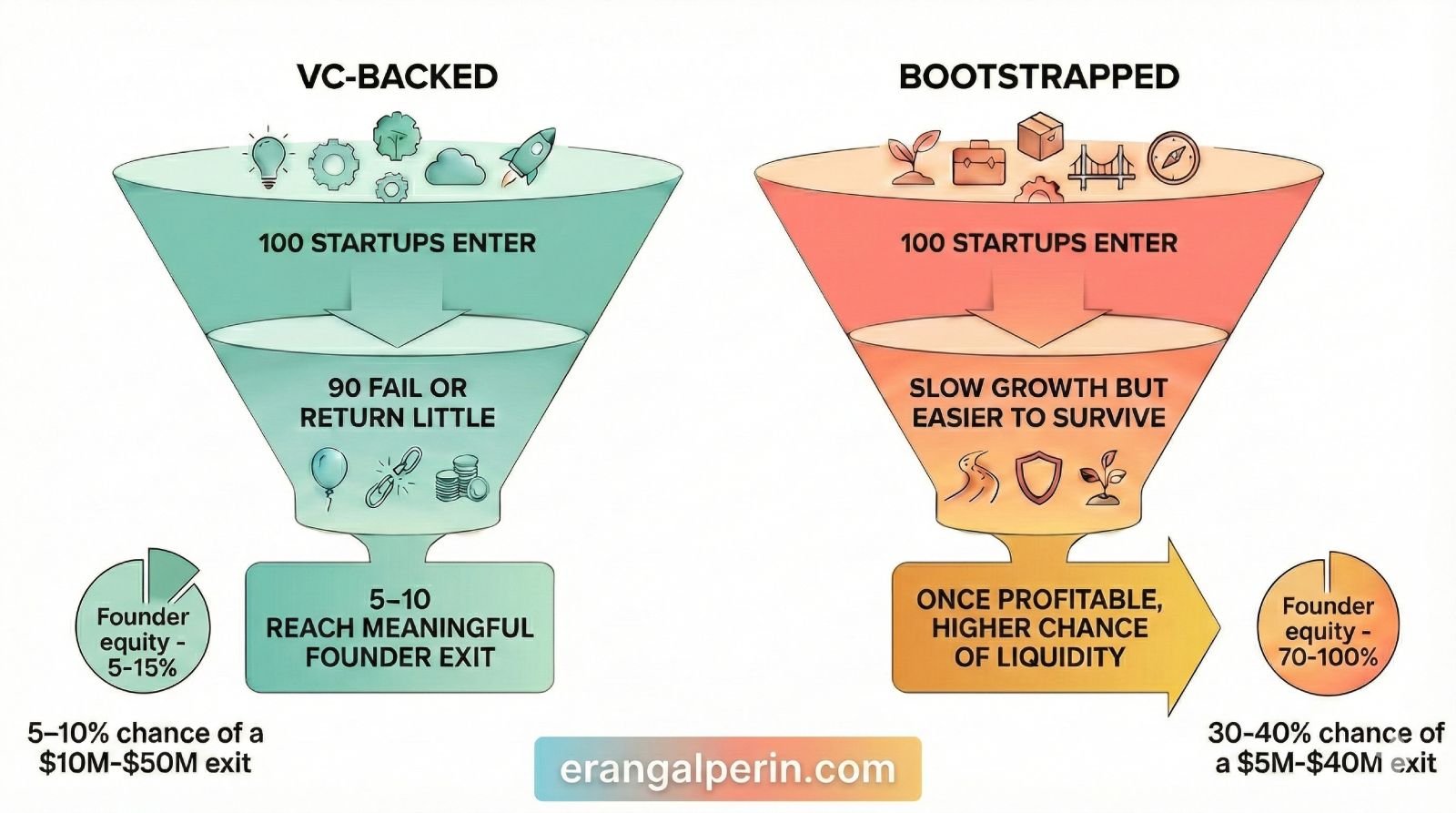

Most VC-backed startups have multiple co-founders, raise several rounds of capital, and refresh option pools along the way. By the time they reach an exit – if they reach one at all – founders often own 10–20% of the company collectively, and frequently less.

Split across two or three founders, that often translates to single-digit ownership per person.

Add liquidation preferences on top, and the picture becomes even more fragile. It’s entirely possible for a company to sell for tens – or even hundreds – of millions of dollars and still deliver little or nothing to common shareholders (i.e, founders). FanDuel is a well-known example: a roughly $500M exit that reportedly resulted in no payout for the founders due to the accumulated preference stack.

Bootstrapped and lightly funded companies operate under very different constraints. They tend to have smaller founding teams, cleaner cap tables, and far higher ownership at exit- often 50–100%. The exit values are usually lower in absolute terms, but the outcomes for founders are often comparable, and sometimes better, on a personal level, and with much higher rates of founder liquidity.

This is where the conventional narrative breaks down.

What the Outcome Math Actually Looks Like

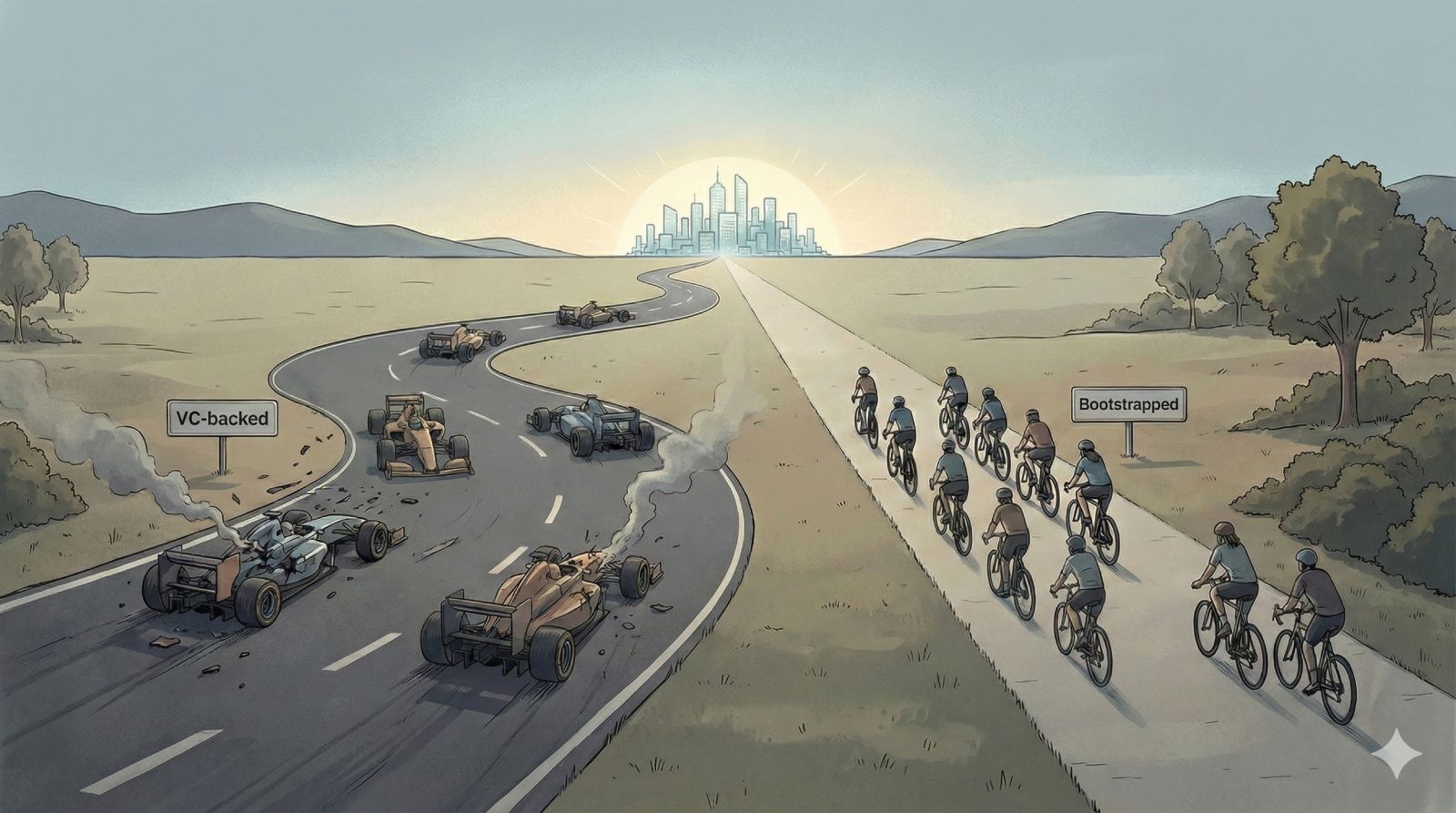

At a high level, the two paths optimize for very different things.

- Venture capital optimizes for rare, extreme outcomes

- Bootstrapping optimizes for durability and optionality

Once you factor in dilution, co-founder splits, liquidation preferences, and exit probabilities, the difference becomes easier to see.

Illustrative, back-of-envelope comparison of founder-level outcomes across VC-backed and bootstrapped paths.

The headline numbers surprise many founders the first time they see them laid out this way:

- VC-backed startups produce larger headline exits – but meaningful founder liquidity happens in a small minority of cases.

- Bootstrapped and lightly funded companies exit at lower valuations – but do so more frequently, with far higher founder ownership and fewer structural obstacles to getting paid.

A founder owning 70% of a $30M business doesn’t need a venture-scale outcome to reach a life-changing result. They just need a business that works.

The Exit Spectrum Most Founders Never See

Another blind spot in tech is how narrow the imagined exit looks.

When founders think about exits, they tend to picture a single event: the acquisition, the IPO, the finish line. In reality, exits exist on a wide spectrum:

- Partial liquidity

- Founder-led buyouts

- Minority growth investments

- Roll-ups

- Strategic acquisitions that prioritize cash flow over growth narratives

Once you stop optimizing exclusively for venture outcomes, this spectrum becomes visible – and accessible. Many of these exits happen earlier, with less risk, and with far more founder-friendly dynamics than the canonical VC endgame.

They’re just quieter.

(I previously wrote on the various types of acquirers)

Why This Market Remains Invisible in Tech

This isn’t a conspiracy. It’s structural.

Tech media amplifies venture outcomes because they’re visible and exciting. Accelerators and ecosystems are funded by VC, so they teach VC logic. Founders learn from other founders – who raised VC. And buyers of profitable businesses don’t often go on podcasts to share their “wisdom”.

The companies acquiring bootstrapped SaaS businesses don’t need to recruit founders. They simply wait for businesses to reach a certain level of maturity- and then conversations start privately.

By the time many founders encounter this market, they’ve already locked themselves out of parts of it.

When Venture Capital Does Make Sense

Venture capital isn’t inherently good or bad. It’s a specialized tool — and in some cases, it’s the right one.

Capital-Intensive Markets

Some businesses simply can’t be built without large upfront capital. Hardware, biotech, energy, and infrastructure often require years of development, manufacturing, regulatory approval, and supply-chain investment before meaningful revenue exists.

In these markets, bootstrapping isn’t conservative – it’s usually impossible. VC exists to fund exactly this kind of risk.

Winner-Takes-All (or Winner-Takes-Most) Markets

In certain markets, speed and scale matter more than efficiency.

Network effects, marketplaces, and platforms can reward the first company to reach critical mass. When the market genuinely converges on a small number of dominant players, raising capital to grow faster than competitors can be rational – even if it introduces dilution and risk.

Highly Speculative Markets Without a Clear Business Model

Some categories are speculative by nature.

Frontier research, early crypto, or entirely new consumer behaviors often don’t have a clear path to revenue at the outset. These bets resemble research more than traditional business building.

VC is well suited to this kind of uncertainty because it’s designed to absorb failure in pursuit of rare, outsized successes.

The Real Question Isn’t “VC or Not”

The mistake most founders make isn’t raising venture capital.

It’s raising it by default – without asking whether their market, business model, and personal goals actually match what VC is optimized for.

For capital-efficient SaaS businesses with clear customers and predictable revenue, VC is often optional. Sometimes helpful. Sometimes harmful.

The point isn’t to avoid VC, it’s to choose it deliberately.

A Personal Observation

When I sold my own bootstrapped SaaS company, what surprised me most wasn’t the outcome itself – it was how wide the non-VC buyer universe was, and how little it resembled the narratives most tech founders absorb early on.

- Real business metrics are much more important than pie-in-the-sky dreams

- Slow and steady growth is sought after rather than seen as a sign of failure

- Founders are given optionality in their role post acquisition

The exit wasn’t possible despite not raising venture capital.

It was mostly possible because of it.

A Better Question to Ask

Instead of asking, “Should I raise VC?” a more useful question is:

“What constraints am I willing to accept in exchange for this capital?”

Capital decisions aren’t neutral. They lock in expectations, timelines, and acceptable outcomes – often long before founders realize it.

For many companies, especially in SaaS, staying capital-light for longer doesn’t reduce ambition. It preserves freedom and expands the range of meaningful outcomes for founders.

Closing

Venture capital is a powerful tool.

It just happens to be optimized for a narrow slice of companies and outcomes.

Most startups don’t fail because they didn’t raise VC.

They fail because they committed early to a path that eliminated flexibility – without fully understanding what they were giving up.

The real advantage isn’t bootstrapping or raising or selling.

It’s optionality.

And most founders have more of it than they think – until they trade it away.